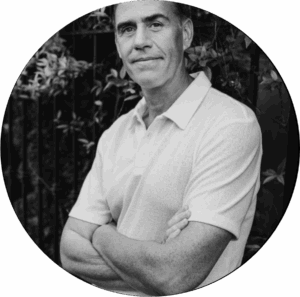

Little Wisdoms, Big Change – Dr. Paul Chadwick

From how to build a cracking team, to unearthing the kernel of insight that was pivotal to a behavioural change intervention, this series from Claremont is an opportunity to hear from the brilliant minds working to bring about positive social change.

Dr. Paul Chadwick – CEO of Behavioural Science and Public Health Network, Consultant Clinical Psychologist and Honorary Associate Professor at the world-renowned UCL Centre for Behaviour Change.

Q1. What’s one thing you learnt early on in your career that has stuck with you ever since?

I’m a clinical psychologist and spent most of my early professional life on wards and community settings assessing patients with neurological conditions. It taught me that there is a big difference between what people say and what people do, the limitations of self-report, and the importance of gathering multiple perspectives before coming to a conclusion. Direct observation is the most powerful tool we have for understanding behaviour but is too often neglected in favour of questionnaires or interviews. I always try to find a way to observe any behaviour I am tasked with changing.

Q2. What insights sit at the heart of some of the work you are most proud of? How did you find them?

I’m a big advocate of deep engagement with the behaviour you are trying to change, and the benefits of drawing upon one’s own and other’s lived experience. My best work has come from hanging out with people in their homes, their places of work and where they spend their leisure time, and remaining deeply curious about why people behave in ways that they do.

Q3. What skills, values or attributes are needed in a team seeking to bring about positive change and why?

The most effective teams consist of individuals who attempt to understand the perspectives, practices and methods of their teammates, and are willing to work across professional and disciplinary boundaries. This requires psychological flexibility and curiosity in the team members and a culture that creates a psychologically safe environment for people to explore and take risks.

Q4. What is your favourite behaviour change / social good campaign from the last 12 months and why?

There’s a lot of great recent campaigns, so it’s difficult to choose. I’d like to mention two early adopters of a behavioural science approach to public health campaign development. Safefood Ireland’s ‘It Takes a Hero’ campaign is a brilliant example of how to reframe parental responses to managing children’s eating behaviour in an obesogenic environment. Samaritans ‘Small Talk Saves Lives’ campaigns is a fantastic example of how a behaviourally informed comms campaign could enhance efforts to prevent suicide on the UK rail network.

Q5. If you could change one thing about the past, present or future, what would it be?

This might be controversial. I think everyone involved in attempting to change the behaviour of others should be required to have training in reflexive practice. These methods help people understand how their background and experiences influence their understanding of the behaviours they are being asked to change, and to consider the wider implications of the interventions they create. Reflexivity is the most effective way of ensuring the ethical foundations of behaviour change practice.

Q6. What have you read / watched / listened to lately that you have found particularly insightful?

I love the poem ‘The Patience of Ordinary Things’ by Pat Schneider. It reminds me of the importance of looking with fresh eyes at what you think you know, looking for what is new and possible about a phenomenon rather than what you have been conditioned to see. Great behaviour change is the art of seeing what is possible over what is probable. Poetry, art and literature (along with reflexive practice) may be our best defence against ineffective, mechanistic and reductionistic approaches to changing behaviour.