Notre just any old cathedral

Notre-Dame was more than just a tourist attraction – it was, and still is, the symbolic icon of France. And so, when its 12th Century foundations surrendered to the flames last month the world held their breath. This wasn’t just an economic loss, it was a historical, emotional and psychological one that echoed across the Western world.

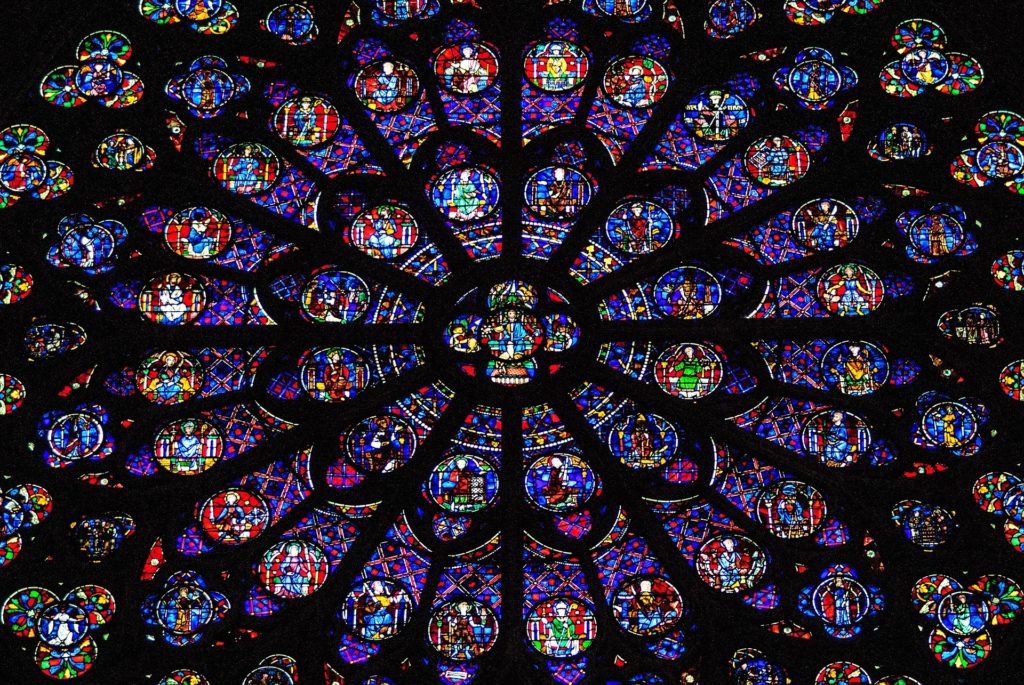

It took 500 firefighters 12 hours to control the blaze and although the two bells and a large part of the iconic stained glass windows were saved, the 315 foot oak wood spire and a lot of the wooden roof were not so lucky. The loss people felt spread internationally and within hours, donations were pouring in for its renovation – including significant pledges from Gucci, Apple, L’Oreal and two of France’s wealthiest men – François-Henri Pinault, CEO of Kerin, and Bernard Arnault, CEO of LVMH Group (who between them gave 300 million Euros).

The public took to social media to ramp up the push for contributions, and donation sites such as Fondation du patrimoine (which, interestingly, anchors the first donation suggestion at 50 Euros) were quickly set up.

The impact resonated across the Western world…but why? Why have we been so traumatised by the burning of a building? Why has the public emptied their pockets for the loss of some gothic artefacts and art when no lives were lost? Surely humanitarian emergencies or tackling poverty are more worthy of donations? In just two days more than $1 billion (£774 million) had been donated to Notre Dam’s rebuilding; six months after the burning of Grenfell just £26.5 million had been donated. What is going on here?

The importance of salience

From a behavioural perspective, the reaction is intriguing. People grieve when they lose something of importance to them. One could, therefore, understand the distress felt by Parisians who see the cathedral every day on their way to work, or the population of France who hold it close to them as an icon of their history and culture. So why did people who weren’t ‘physically’ close to the building feel the pain?

Put simply, it’s because the cathedral was, in some way, emotionally salient to them; especially so for the millions of tourists who have visited while on holiday, Catholics who have learnt the grandeur of its religious holding or students who have studied its gothic artefacts. Even many who have never stepped foot in France, but feel familiar with Paris through Western culture and literature, could immediately imagine the size of this loss to a city so loved around the world.

If someone can relate or feel a personal connection to something, then its importance, and therefore in this case, its loss, will resonate with them. It’s why you’re more likely to donate to a Parkinson’s disease charity if a friend has Parkinson’s, regardless of how often you see them.

Why this cause and not others?

Not long after donations started coming in, counter reactions started appearing. The most obvious were the outcries from the ‘Gilets Jaunes’ who, despite their ongoing protests, have not gained traction in their fight against social insecurity. Furthermore was the frustration around other horrific events that didn’t attract anywhere near as much attention, but where lives were lost. Should I mention Grenfell again? What about the levelling of the ancient sites in Xinjiang or the shattering community and rising death toll in Aleppo?

The sad reality is that, despite the horror of these incidents, most people who represent the top tier of philanthropy can’t psychologically relate to these situations. We see the pain and loss in Aleppo, and poverty on the news, but many in the West with the resources to help have no emotional connection to them. They are too far removed.

With Notre-Dame, people clearly felt that connection. But it wasn’t just salience that drove the scale of response. Unlike intractable issues like poverty, ‘fixing’ this problem also feels tangible and possible with enough money. Charities scrapping for their share of public generosity will know this challenge well – to part with cash, donors need to believe their money will make a difference, as much as care about the cause.

So what does this mean for behaviour change comms?

The moral of this story is that people have a limited scope of cognitive and psychological load – and the first job of any piece of communications is to get noticed. If you want to change behaviour, you first need to emotionally and psychologically connect with your target audience.

This means you need to make sure you really understand who you’re trying to reach. How their life experiences influence their thoughts, emotions, beliefs and most importantly, behaviour. You need to find out what is emotionally salient TO THEM and then link that to the behaviour change you’re seeking.