Flawed by Design: Is AI just as biased as we are? And is behavioural science doomed?

A special quirk that we all share is that we’re all incredibly biased. This fascinating foible has fuelled the creation of an entire academic field: behavioural science. Human biases have been meticulously examined, named and codified; they have been used to explain our decision-making and to thereby design our environments.

You’d probably think then, that if we humans designed artificial intelligence (to make our lives better, faster and more efficient), that we would prioritise making this technology ‘bias free’. Well you’d be wrong. As it turns out, AI can be incredibly biased. Let’s delve into why.

Firstly, AI learns from human data. Take an AI image generator for example, which relies on vast datasets scraped from the internet to learn about patterns and styles. Without this process, the AI might produce an image that isn’t as pleasing to us, as its human overlords. However this also opens the door for a huge degree of bias, as Buzzfeed experienced with its now deleted article showing AI depictions of Barbie dolls around the world. These dolls displayed extreme forms of representational bias, particularly racist depictions. For example, some questioned why South Sudanese Barbie was holding a semi-automatic pistol, while others wondered why Kuwait Barbie was wearing a male headdress.

And this picture might be even worse than we feared. Researchers from UCL have recently discovered that AI trained on human-biased data not only replicates these biases but actually magnifies them. Biases that were amplified by AI systems included underestimating women’s performance and overestimating the competence of white men. I recently attended an event hosted by the UN Innovation Nework which spoke to these gender biases. One piece of research found that many LLMs associate men as “more gifted in maths and science” and women as “more gifted in humanities”. And this isn’t a ‘Western problem’: this finding held across multiple counties and across various languages.

The second reason that AI can be biased is more upstream. AI creators and designers can themselves bring assumptions and biases to the design process. Under 14% of people working in the machine learning field are female, according to Design Week, and “datasets used for technology are taken from clinical trials which are ‘notoriously white male centric’.” How does this trickle down? A few years ago, the Harvard Business Review looked at voice-enabled AI assistants. They found that while a white American male had a 92% accuracy rate when it came to being understood, a white American female had only a 79% accuracy rate. A mixed-race American woman had only a 69% chance of being understood. Similarly, it’s more profitable to design voice technology systems for English speakers so an ‘English first’ approach often prevails.

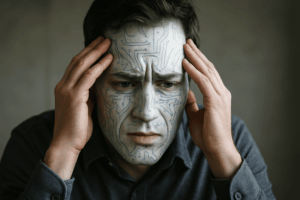

As an aside, the image above was the first one generated by ChatGPT for this blog. When I questioned why it had chosen a white male, when I hadn’t specified, it said: “The image defaults to a white male appearance because, unless otherwise specified, image models tend to reflect dominant visual biases from the datasets they were trained on.”

So is this all doom and gloom? Not completely. Biases are context-specific, so what’s biased in one context could be appropriate in another. For example, in some cases it might be appropriate to design for speed over accuracy, like in a fraud detection system. In other cases, the context might change and that might create a new bias. For example, you might design for speed over accuracy when creating a facial recognition AI that spots criminals, because that seems urgent, but that software might be more likely to misidentify black and female faces as a result. There’s no perfect formula, but are there at least opportunities?

For behavioural scientists and experts, I believe that there are opportunities. We are best placed to spot systematic biases that others might miss. We are well versed in looking for unintended consequences from design decisions that others might consider to be ’neutral’. We hold the insights that will enable AI to be ‘human-first’: we understand how people act in the wild, with limited information and often under cognitive stress. AI will shape the future of human behaviour but we, in turn, can shape the future of AI.